Wharton Researchers Build Algorithm to Help Fight Sex Trafficking

A pair of Wharton researchers are using machine learning to shine a light on sex trafficking, one of the darkest and most difficult crimes that claims millions of victims a year worldwide.

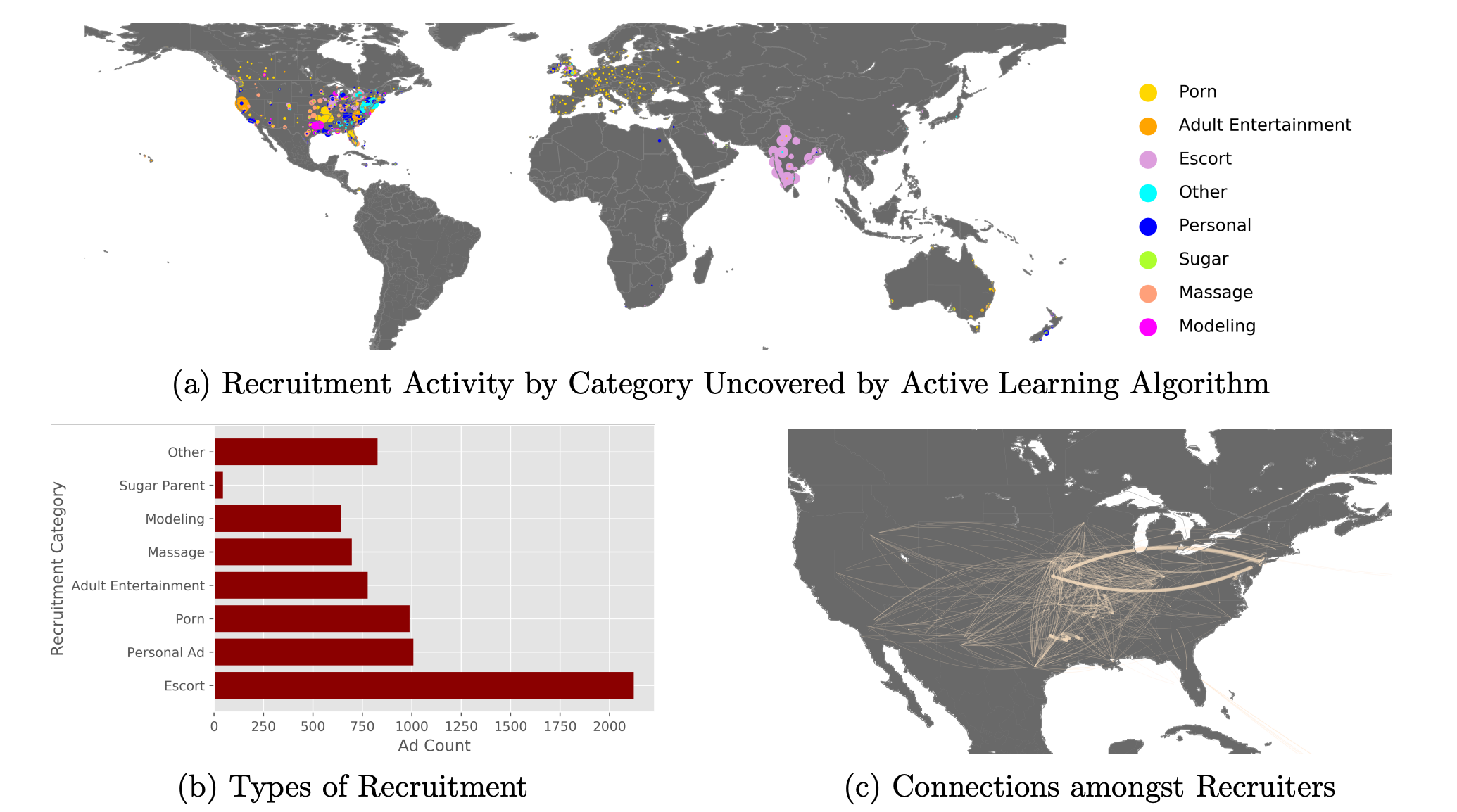

Pia Ramchandani, doctoral candidate in the Department of Operations, Information and Decisions, and her professor, Hamsa Bastani, are developing algorithms to help law enforcement crack the code on covert networks that recruit victims through deceptive online ads. Those ads appear to offer legitimate work, such as modeling or massage, then force respondents into sex sales.

“We’ve been looking at how we can use big data to help improve counter-trafficking tactics,” Ramchandani said. “Specifically in this project, we were looking at can we use big data to identify commercial sex supply chains — where recruitment is happening and where sex sales are happening.”

She and Bastani found that much of the recruitment happens in lower-income, smaller cities and feeds into bigger cities, such as from Scranton to Philadelphia or Long Island to New York City. They also found cross-country pathways, such as from Australia and Canada into the United States.

“Some of those findings were surprising to our collaborators,” Ramchandani said.

“The biggest challenge that I’ve had is trying to think about the impact of the work and designing it in a way to maximize benefit and minimize harm [to commercial sex workers].”

– Pia Ramchandani, doctoral candidate, Department of Operations, Information and Decisions

The results are in a paper co-authored with Emily Wyatt, co-chair of TellFinder Alliance, a technology platform for law enforcement and nongovernmental organizations that scrapes the web for trafficking data. TellFinder provided Wharton with more than 14 million posts from across the deep web, which is identified as the parts of the web not indexed by traditional search engines.

“There’s a lot of interest in being able to leverage big data, in this case deep web data, to give visibility into these opaque supply chains,” said Bastani, a professor in the Department of Operations, Information and Decisions. She said the data culled from deep-web ads is key to the research because it helps separate trafficking victims from other kinds of commercial sex workers who may be willing participants in illegal activity.

“The problem is that commercial sex work that’s consensual and human trafficking often gets conflated,” Bastani said. “That’s really important because commercial sex workers are already an exploited population. Also, law enforcement has really limited resources and really want to go after traffickers.”

Including All Stakeholders

Ramchandani and Bastani said they did not want to develop their methodology in a bubble. It was imperative they include the perspectives of all stakeholders, including law enforcement, the nonprofits who work to rescue victims, and even the victims themselves. Those conversations helped them understand how trafficking flows between cities, which helped them set up their research.

“The way we designed our methodology completed changed to prioritize network discovery over specific entity risk accuracy,” Ramchandani explained. “One big part of it is talking to people and trying to understand the nuances. Another part of it is just going back and forth between the data and your algorithms.”

“The problem is that commercial sex work that’s consensual and human trafficking often gets conflated. That’s really important because commercial sex workers are already an exploited population.”

– Hamsa Bastani, Assistant Professor, Department of Operations, Information and Decisions

The scholars spent countless hours running trials, examining the results, and redesigning the algorithms to get everything right. The ultimate goal, they said, was to “train” the algorithms to hit the right target through the right keywords.

“The biggest challenge that I’ve had is trying to think about the impact of the work and designing it in a way to maximize benefit and minimize harm [to commercial sex workers],” Ramchandani said “The way you design algorithms, they can have bias in them against particular groups. Or the way they could be used could unintentionally raise focus on a certain set of people.”

Bastani said the project has implications beyond sex trafficking. Similar methodology is being used to target labor trafficking on the high seas, for example.

She said the more input and data that researchers can gather from stakeholders, the better the algorithms will be. But that kind of precision takes funding, which is always in short supply, especially for financially strapped law enforcement agencies and nonprofits. For this project, Bastani and Ramchandi received funding from the Wharton Social Impact Initiative and additional financial support from Analytics at Wharton.

“If we could fund an intern at a nonprofit to actually conduct outreach to sex workers to see who is at risk, that would give us much higher quality data,” Bastani said.

Ramchandani agreed, saying she would like to include sex workers directly in the research to talk about their experiences.

“There’s a whole space of participatory research where you actually include the voices of the people being impacted so that you make sure you’re designing it in a positive way,” she said. “I would love to be able to actually fund them for their time.”

– Angie Basiouny