Wharton Research Shows Revitalizing Vacant Lots Pays Dividends

“The reality is quite intuitive,” says Matt Rader, WG’11, President of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS). “If you think about living next to or walking past a lot that’s unmaintained, dumped on, filled with weeds, versus one that is clean, green, fenced, and welcoming to you, it’s a major difference. It really transforms community life.”

That’s the guiding principle behind PHS’s Philadelphia LandCare program, an initiative to work with local businesses and communities to transform the tens-of-thousands of abandoned parcels of land in Philadelphia into attractive, well-manicured micro-parks through a process called “greening.” While the aesthetic benefits to this process are indeed intuitive, researchers at The Wharton School suspected there might be more than meets the eye, as they sought to gain an analytical understanding of the LandCare program’s benefits.

“This particular vacant lot greening initiative provides us with a really nice, almost experimental situation for evaluating what impact small changes in a neighborhood can have on various types of neighborhood outcomes,” says Shane Jensen, professor of statistics and data science at Wharton. “Susan [Wachter] and I got involved specifically…because we were interested in real estate value and the potential change in housing prices that can be impacted by greening lots.”

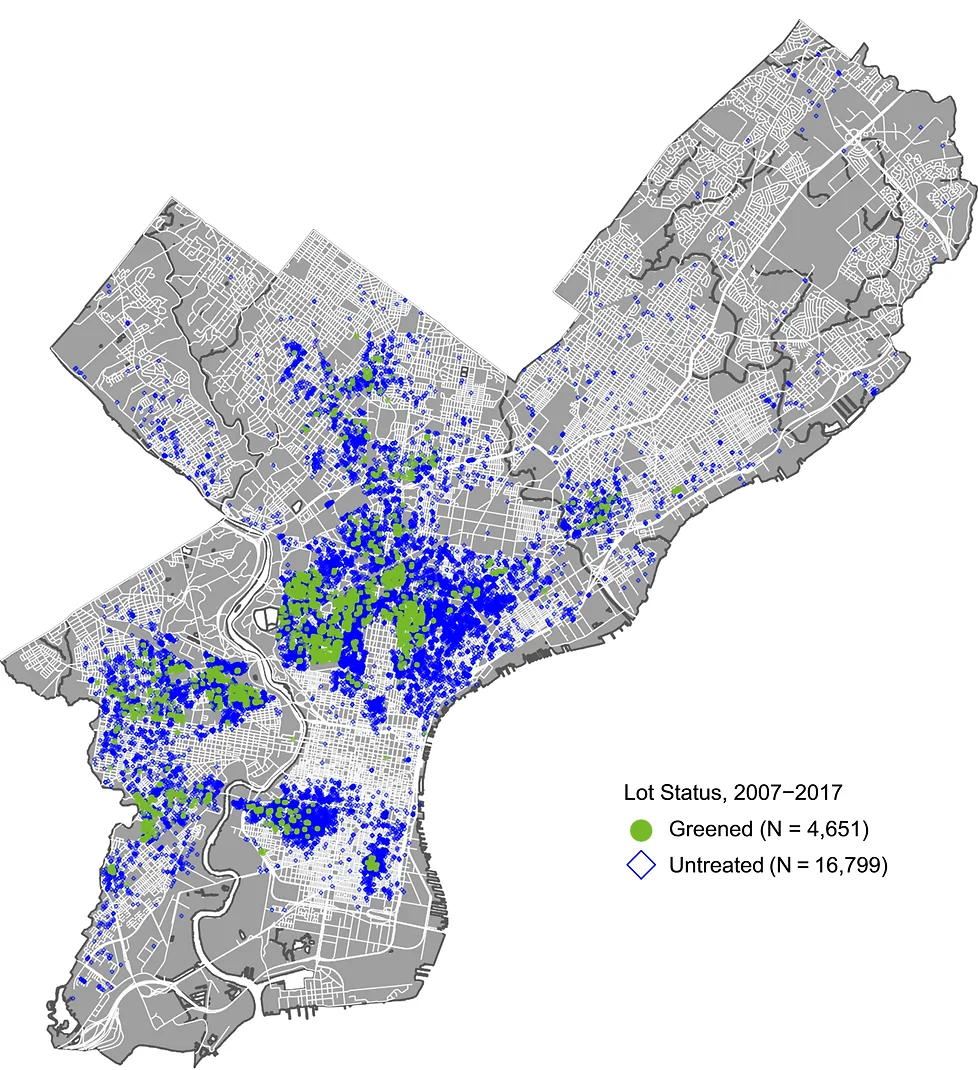

With research funding from Analytics at Wharton, Wachter, the co-director of the Penn Institute for Urban Research (IUR), worked with Jensen and Desen Lin, her former student and current assistant professor of finance at California State University, Fullerton. In a research paper published in July of 2022, the team compared 4,651 lots that had been greened from 2007-2017 against a control group of 16,799 untreated lots from that same period.

“For nerds like us it’s just hysterical fun, actually, because we just don’t know what the data is going to tell us.”

– Susan Wachter, Co-Director of the Penn Institute for Urban Research, Professor of Real Estate, Professor of Finance

“Our challenge with the analysis and data was to try and come up with – for these lots that actually had been greened – the best possible comparison group to isolate the impact of this greening intervention,” says Jensen. With so many neighborhood attributes – population density, access to public transportation, economic context, and more – it was difficult to arrive at an “apples-to-apples” comparison for each of the greened lots. To solve this issue, the team utilized weighted linear regression modeling, a type of statistical methodology that is helpful for determining how one variable affects another.

For some, this type of intensive analysis might seem intimidating, but at Wharton, it’s a blast. “For nerds like us it’s just hysterical fun actually,” Wachter says with a chuckle, “because we just don’t know what the data is going to tell us.”

What the data told them exceeded expectations. Properties within a 1,000-foot radius of a greened lot experience, on average, a 4.3% rise in value after the first year and a 13% cumulative increase after six years. Furthermore, the team’s research indicates that there are an average of 18 homes within a 1,000-foot radius of a greened lot, with a median value of $250,000. That means the increase in value of those properties totals a combined average of $193,500 in just the first year alone.

While raising property values isn’t necessarily the intended purpose of the Philadelphia LandCare program, it’s easy to see just how cost-effective the program is: the cost to green a lot is $2,500, and annual maintenance is roughly $400, a total price that is orders of magnitude lower than the exponential value it creates.

Because vacant lots are often highly concentrated in neighborhoods with lower median household incomes, skeptics of this greening initiative might question if these numbers signal gentrification. In reality, the economic aspect of this program only affects a small portion of a neighborhood’s population, and the property value increase – which is not pervasive enough to contribute to displacement of a large number of residents – works to reclaim some of the value these neighborhoods have lost through disinvestment.

“We’re not coming in their neighborhood for gentrification, or [to do] something they don’t want us to do,” says Keith Green, senior director of Philadelphia LandCare and workforce development at PHS. “If they want us there, we will work there. If they don’t want us there, we won’t do the work.” It’s this type of collaborative community spirit that ensures greened lots are a shared asset for all members of a neighborhood, not just those who own property.

“We’re not coming in their neighborhood for gentrification, or [to do] something they don’t want us to do.”

– Keith Green, Senior Director of Philadelphia LandCare and Workforce Development, Pennsylvania Horticultural Society

“I tell this story all the time, people laugh when I say it,” Green says. “I once saw someone walking his snake on the [greened] lot. He said he does this because he wanted his snakes to crawl like they’re in their natural habitat. I was like ‘people aren’t going to believe this. You can’t make this story up…’ You see horses grazing on the lots, kids playing football on the lots… you see this year after year. This simple treatment transforms a neighborhood and gives people an opportunity to have something that they didn’t have before.”

For PHS, studies performed by Penn and Wharton help to quantify the benefits greened lots provide. Additional research by John MacDonald, professor of criminology and sociology, reveals that neighborhoods with greened lots “experienced 29% less gun violence, 22% fewer burglaries, and a 30% drop in issues like illegal dumping.”

“The partnership with Penn is a great collaboration and has helped us to sustain this impact year after year,” says Rader. “Research done by Dr. Wachter and others help make the case for greening interventions from the beginning. We have many people actively involved today as funders and board members who first encountered PHS’s work through conferences hosted by Wharton and PennIUR.”

“When you’re here,” says Wacther on a tour of a greened lot, “you can see the benefits in terms of a community asset. It brings hope. It brings a sense of future, as opposed to a trash-strewn lot which comes with a sense of despair. This is a testament to the folks at PHS who have been long dedicated to making this happen, one lot at a time, for the people of Philadelphia.”

While the Philadelphia LandCare program may be simple in design and substantial in execution, there’s still plenty of work left to do. “These are things that need to be sustained year after year,” says Rader. “I’m really proud of the impact we’ve created but I think as a city and region, we’ve only tapped – just, just tapped – the potential of these [lots] to make changes in our neighborhoods. Unlike a lot of projects where people want to think about it as ‘I make a two-year grant, I make the impact, and it’s done,’ this is work that has to keep happening year after year, day after day, and sustaining the energy and helping people find the growth path is a critical part of what we do.

If you’d like to get involved in the Philadelphia LandCare program or other initiatives to improve health and well-being in the greater Philadelphia region, visit www.phsonline.org.

—

Updated February 6, 2023