Measuring Vehicle Exhaust Standards Over Time

Wharton professor Arthur van Benthem is no gearhead, but you’d never guess that from the passionate way he talks about cars.

“I can fill my tank. That’s about it,” he cheerfully admits before launching into a detailed explanation about the jaw-dropping improvement in vehicle exhaust emissions over the decades.

No, it’s not torque or horsepower that excites van Benthem, a professor of business economics and public policy whose research focuses on energy and environmental policies. It’s the results of his study into 50 years’ worth of vehicle emissions data – literally hundreds of millions of data points – that get him fired up.

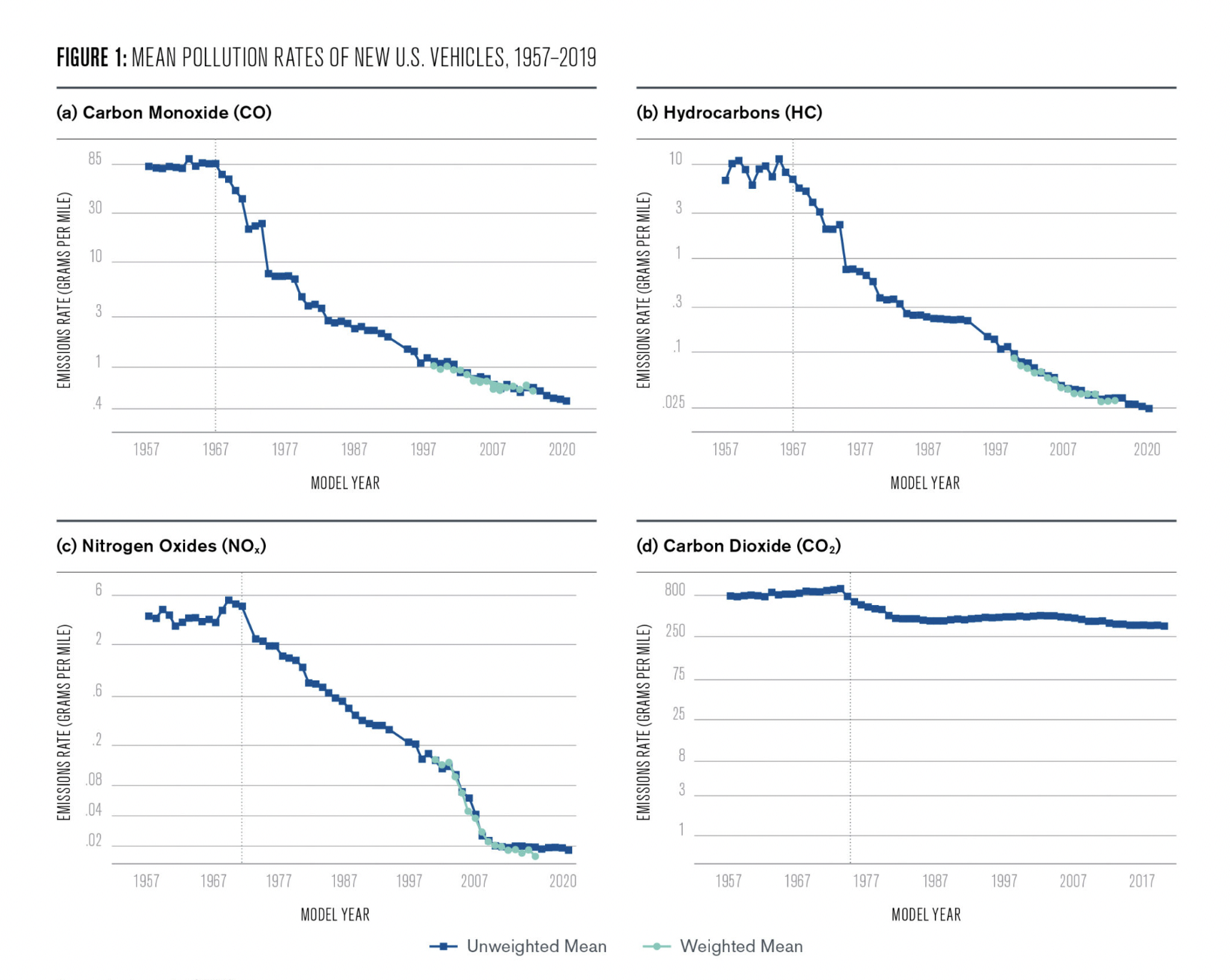

“An average new vehicle today emits about 200-times less than an average new vehicle in the 1960s.”

The co-authored study, which was published in December 2022 by the National Bureau of Economic Research, found that local air pollution emissions from vehicles – consisting of carbon monoxide, hydrocarbon, and nitric oxide – in the United States have fallen by more than 99% since 1967 under standards first imposed by the Clean Air Act. In fact, the average new vehicle today releases about 200 times less pollution than a car built in the 1960s, according to the study.

That’s good news, van Benthem said, and proof that government regulations can work to benefit the environment. Besides local air pollution, transportation also accounts for 27% of all greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., which is more than any other economic sector.

“Our research uncovered that most of the [vehicle emissions] decline is actually caused by these standards, so the government policy has been quite effective,” van Benthem said.

Unfortunately, the professor and his co-authors also uncovered a steep increase in emissions from cars as they age, racking up the miles while their pollution control systems degrade.

“Once a car is on the road, it gets much dirtier as it ages, especially when it reaches 15 to 20 years,” he said. “Those super-polluters are responsible for a huge share of emissions in the U.S. fleet. That’s why we concluded we need to supplement these standards with other incentives to try to remove some of those super-polluters from the road.”

Van Benthem, who also serves as co-director of the Wharton Climate Center, is dedicated to the pursuit of science that helps both industry leaders and policymakers put stronger environmental guidelines in place. Federal regulations are far-reaching and often tinged with contentious politics, so he thinks it’s important to bring academic rigor to the debate. For van Benthem, an economist and self-described concerned environmental citizen, the right answers usually can be found in the research.

“You may think I’m sitting here in deep thought, writing mathematical formulas every day, but in reality I spend a lot of time chasing government agencies and asking them to share their data with me.”

State and federal agencies “had very little information about these policies to start with, so our study has filled that gap. We’ve also been able to make recommendations about other policies that might reduce emissions further beyond just the exhaust standards we have today,” he said.

The emissions study, which was funded in part by Analytics at Wharton and the Wharton ESG Initiative, took five years. The co-authors collected real-world data from inspections and emissions tests, which capture exhaust pollutants under simulated driving conditions. They then examined variables such as tighter fuel economy standards to determine whether other factors accounted for the dramatic emissions drop over time.

“For this research, we had to go on a major data hunt,” van Benthem said. “You may think I’m sitting here in deep thought, writing mathematical formulas every day, but in reality I spend a lot of time chasing government agencies and asking them to share their data with me. Sometimes it’s a long, bureaucratic process, but in general there’s always interest on their side to get their data to researchers and uncover new patterns and information about how their policies have performed.”

Although the study examined historical data, the results look forward because they have implications for automakers designing new cars and trucks to bring to the market, especially as the older super-polluters phase out.

“It becomes more attractive to sell new electric vehicles and other clean cars as the used-vehicle fleet gets smaller and people substitute away from used cars toward those new cars,” van Benthem said. “So, automakers should be interested in supporting polices that clean up the used-car fleet.”

The professor said he hopes his research also helps policymakers consider financial incentives to curb pollution, such as the carbon border tax recently adopted by the European Union.

“I think it’s very important that we don’t dismiss the idea of pricing pollution as quickly as we’re doing today in the United States,” said van Benthem, who emigrated from the Netherlands. “It’s politically very difficult, but the end result is that the kinds of policies we choose in the U.S. may end up being much more expensive for society than the policies that are maybe politically less popular but implemented in other parts of the world. I think it’s a lost opportunity that we are so shy about using taxation for environmental purposes.”

Van Benthem is currently studying the markets for renewable energies, oil, and gas. Read more about his research at Knowledge at Wharton.

– Angie Basiouny